Attention

The contents of this documentation might slightly differ from the information published by Abdol et al., 20211. For general introduction to SAM, please refer to the main publication while we sync the two sources.

Design¶

First, we will review a common process of defining, conducting and reporting scientific research. In this section, we describe a simplified process of producing scientific result. In order to define a list of components and entities involved in different stages of conducting research. Later, in the Design section, we will explain how each component is represented in SAM.

The Scientific Research Process¶

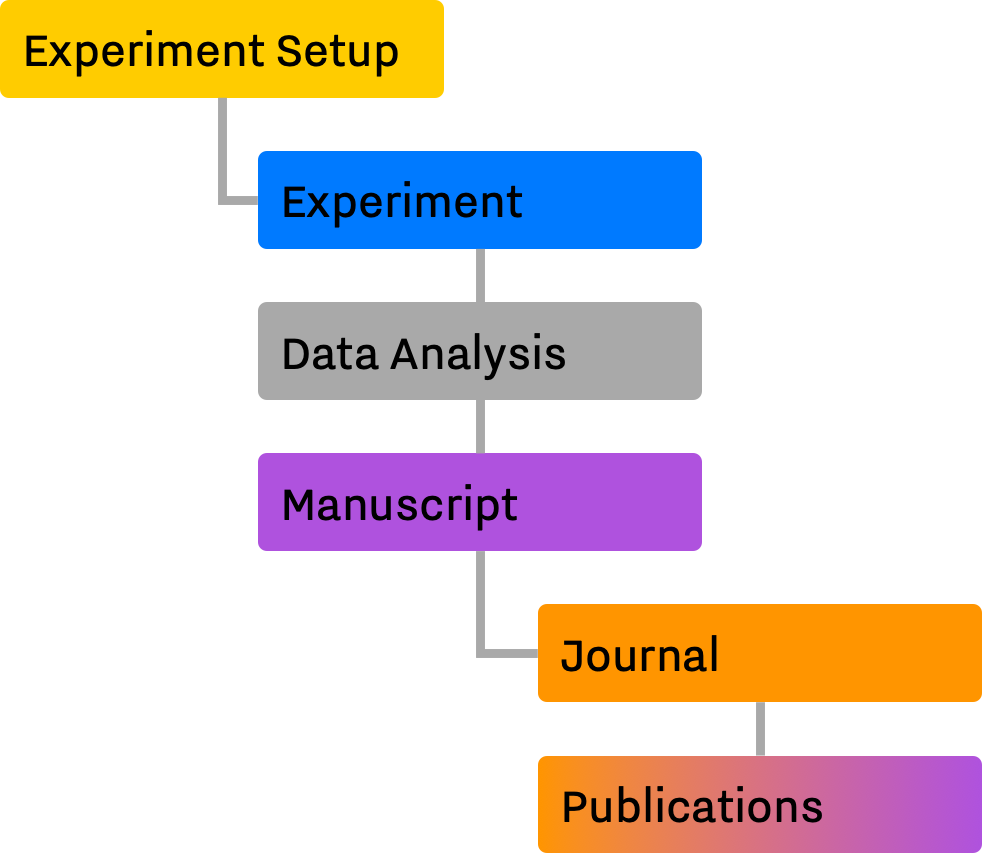

The process of producing scientific research is often a cumbersome and complicated process. A typical scientific study starts by formulating a hypothesis when a Researcher jots down her ideas about how a certain process influences a certain phenomenon or how she thinks a complicated system works. In order to test this hypothesis, she sets up an experiment in which the underlying parameters and boundaries of her theories and ideas are defined.

After the Experiment Setup is finalized, an Experiment is conducted in which the Researcher aims to collect certain types of data in order to test her hypothesis, e.g., questionnaire results, sensors data, images, etc. The next step is (pre-)processing and analysis of the data, which leads to a conclusion evaluating her initial hypothesis (a.k.a results). If the results are informative — regardless of agreeing or disagreeing with the initial hypothesis (i.e., pre-registered hypothesis) — the Researcher selects a Journal and submits her findings in the form of a Manuscript, for it to be reviewed according to the Journal's criteria. Finally, the Journal will decide whether the submitted manuscript is published.

Meta-analysis¶

It has been shown and discussed [cite, cite], the aforementioned process is often long and prone to errors in every different stage. The natural complexity of conducting a research, together with the large number of degrees of freedom available to researchers and journals, will undoubtedly affect the quality of research and publications [cite, cite]. Researchers may make mistakes, and journals may select a particular set of publications based on erroneous or outdated criteria. As a result, various biases will accumulate the pool of publications and ultimately affect our understanding of a certain topic [cite, cite, cite].

Studying this interaction between Researchers, their Research, Journals (i.e. the publishing medium), and Publications (i.e., Knowledge), is a challenging task2,3. The list of degrees of freedom is long4,5 [cite], and researchers are insufficiently aware of the consequences of certain procedures on the final outcome of their research.

In recent years, the field of meta-analysis has grown in size and popularity in an attempt to evaluate and account for the various biases introduced by this process. As a result, the scientific community have defined and documented the effects of researchers' degrees of freedom on published results [cite] and the unwanted outcomes of journals' tendency to publish positive and novel results [cite]. For example, it has been shown that the process of adding new data points to an experiment — after the initial data collection — is a widespread practice4,5 and it has a severe effect on researchers' ability to create significant results; and therefore makes their research more appealing to biased journals, and consequently skew our collective knowledge.

While meta-analysts and statisticians are hard at work to identify and correct for these issues, lack of data and the complicated nature of aforementioned interactions make it challenging to address this issue systematically. To the extend that the scientific community cannot agree on the effects and propagative impacts of questionable research practices on our collective knowledge [cite, papers supporting some of the qrps], a.k.a, true effect size.

SAM¶

With SAM, we are hoping to address this issue. We are developing a standardize and flexible framework for studying of these processes and interactions. SAM streamlines the process of designing and executing large simulation studies covering as many aspects of performing scientific research as possible, from designing the experiment setup to the process of reviewing and accepting research by journals.

-

Amir M. Abdol and Jelte M. Wicherts. Science Abstract Model Simulation Framework. PsyArXiv, 09 2021. URL: https://psyarxiv.com/zy29t, doi:10.31234/osf.io/zy29t. ↩

-

Marjan Bakker, Annette van Dijk, and Jelte M. Wicherts. The rules of the game called psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 76:543–554, nov 2012. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1745691612459060, doi:10.1177/1745691612459060. ↩

-

Marjan Bakker and Jelte M. Wicherts. Outlier removal, sum scores, and the inflation of the type i error rate in independent samples t tests: the power of alternatives and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 193:409–427, 2014. URL: https://doi.org/10.1037%2Fmet0000014, doi:10.1037/met0000014. ↩

-

Leslie K John, George Loewenstein, and Drazen Prelec. Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol Sci, 235:524–32, May 2012. doi:10.1177/0956797611430953. ↩↩

-

Franca Agnoli, Jelte M. Wicherts, Coosje L. S. Veldkamp, Paolo Albiero, and Roberto Cubelli. Questionable research practices among italian research psychologists. PLOS ONE, 123:e0172792, mar 2017. URL: https://doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0172792, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172792. ↩↩